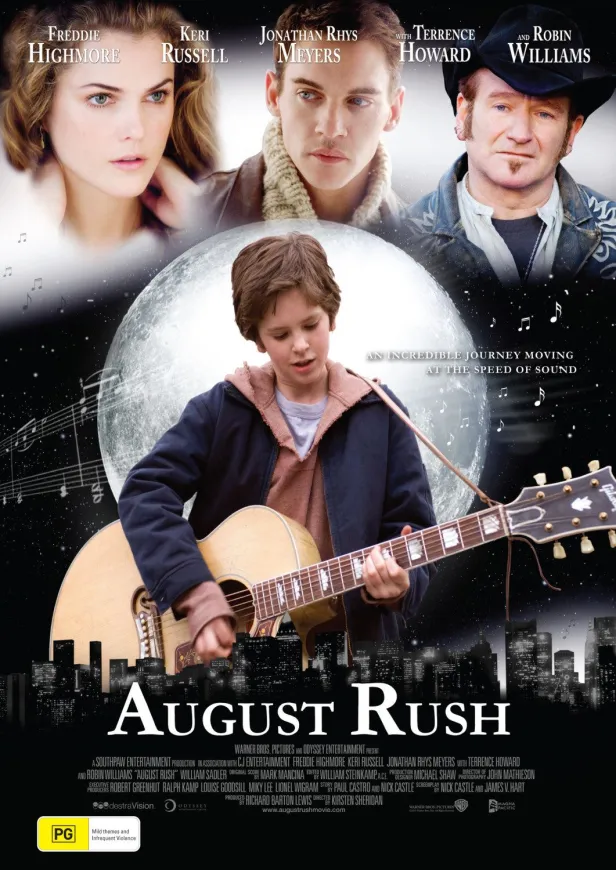

Resident musicologist Max DeCurtins explains how August Rush mythologizes innate musical talent, leading to treacly sentimentality, lousy instrumentation, and Robin Williams in a bizarre hat.

Of the films I’ve re-viewed for this venerable blog over the years, some have sparked derision, some delight; some have moved me anew, some have fallen flat. None has ever left me seething with fury. Until now.

August Rush, people.

August. Fucking. Rush.

I had a pretty good idea of what I was getting into with this re-view, but I confess I wasn’t prepared for my own abject, horrified, visceral reaction to this movie. I’ve possibly never encountered a movie that so grossly exalted its subject and so utterly disrespected it—literally at the same fucking time.

August Rush combines the improbable timing and interconnections of Love Actually with the quasi-religious mysticism of the Force and somehow manages to diminish both. It turns music into one of Those Facebook Memes with a pithy quote set in the faux-painterly Sophia font.

You thought The Notebook was sticky sweet with sentimentality? August Rush is the Great Molasses Flood.* It is, as some critics have suggested, basically Oliver Twist with music. And, as we all know, Dickens stories are definitely not fucked up—no way.

(*Actually a real thing, I promise. And I love molasses. But not in movies.)

I saw August Rush sometime in 2008; I graduated from college the year before knowing that I wasn’t going to be a professional instrumentalist, but otherwise I was undecided between trying to pursue conducting or musicology in grad school. That summer after college I had spent several weeks at an orchestral conducting program in upstate New York, where the point was basically that you got verbally abused by a cranky old white guy. Orchestral conducting has largely been one of those white guy professions—not unlike academia—and if you survive the hazing, it’s vaguely possible you might one day have a career in it. I mostly survived the hazing, but ultimately opted for musicology. Musicology seemed, if you can believe it, the more sensible choice. Of course, the academic career path never materialized; that is to say, neither was I admitted to the terminal degree I needed, nor could I come up with a justification for pursuing a job that almost certainly would be unattainable. So here we are nine years later: Music isn’t part of my livelihood, but Boston is a city of musical plenty and I’ve had eight of those years to get to know lots of people whose livelihood is in music.

Since we’re going to touch on this theme so many times over the course of this movie—and by “touch on” I mean “totally fucking ignore”—I’ll say this just once:

Music is a profession. It is a job. It takes years—if not a lifetime—of constant practice, learning, and refinement. If you choose to make a career of it, we hope, yes, that you’re passionate about it, but that doesn’t make music as a career easier, it just makes it bearable. It’s what makes all of it—the hours you spend practicing; the hours you spend moving instruments (shout-out to the historical keyboardists), or maintaining them, or making parts for them (we see you, double-reed players!); the anxiety you feel every time you have to fly with your instrument(s) (we feel you, string players); the time you spend doing your taxes as a mostly self-employed person (because nobody knows how painful it is); the hours you spend putting together websites (yours, and maybe that group you perform with) and the material for them; the time you spend sending e-mails and asking people for money and doing all your own bookkeeping and administrative tasks (for which, you know, you don’t get paid); the shit you might have to endure to make sure you get paid for that gig you did two weeks ago; the dysfunctional organizational politics of non-profits; the invariably outsized egos that you’ll have to perform alongside or under—worth it. Music is not a “universal language”; at best, it’s a fundamentally human creative impulse that manifests in many different ways across many different cultures, inspiring opinions and ideas in all its many guises. The human instinct for music runs so deep that for many, musical tastes and proclivities are intertwined with their very identity; music may provide transcendental experiences, but by the identity definition they are not universal.

Hereinafter, any time August Rush tosses out an idea that contradicts the preceding paragraph, I am simply going to write: #NOPE.

Now that I’ve gotten that out of the way, allow me to summarize the entire plot of August Rush in one sentence:

August Rush is an orphaned musical savant who believes that Music is basically the Force—some kind of highly emotional, instinctual ur-religion that somehow manages to communicate all the things across time and space—and in this movie, a bunch of people who are fucking miserable and cry a lot and make a lot of highly consequential spur-of-the-moment decisions with nary a moment’s aforethought reunite thanks to circumstances so improbable they make the 2016 presidential election look legitimate.

Knowing what we’re up against, here’s the non-TL;DR version of August Rush, because instead of being a responsible adult and going to bed so I can get over this cold, I’d definitely like to step through the plot of this completely fakakta movie.

The movie opens with Evan Taylor (Freddie Highmore) air-conducting in the middle of a windswept field while his character narrates to us of his musical gifts in a credulous recitation à la Cate Blanchett as Galadriel in the prologue to The Fellowship of the Ring.

Trapped in a New York state orphanage, convinced that his biological parents hear the same music that he hears in everything and thus are fated to reunite with him, Evan narrates that he “believe[s] in music the way some people believe in fairy tales.”

#NOPE

It’s flashback time. The year is 1995. Cellist Lyla Novacek (Keri Russell) and guitarist Louis Connelly (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) meet at a party one night after their respective concerts and have a brief and mostly vapid conversation before having unprotected sex on a rooftop overlooking Washington Square Park, because apparently there were no condoms in 1995 and when you’re two frustrated twentysomethings and sex comes knocking, you answer the door and hope for the best. They’re separated the next morning, and something close to nine months later, Lyla has an argument with her domineering father (William Sadler, who you may or may not have difficulty divorcing from his role as Section 31 agent Sloane in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine) and storms out of a restaurant, whereupon she is promptly hit by a car. The baby is saved, but Lyla’s douchecanoe father puts him up for adoption by the state by forging Lyla’s signature while she’s unconscious and recovering. As he is an amoral sack of excrement, he tells his daughter that the baby didn’t survive the accident. Good times. She gives up performing and relocates to Chicago to teach music. Louis, for his part, escapes his brother’s Irish rock band (it’s not quite clear why he’s so miserable, but his brother being an abusive, manipulative sod might have something to do with it) and ends up in back in San Francisco as some kind of non-specific, intellectually deadened businessman.

Meanwhile in the present, Evan meets child services social worker Richard Jeffries (Terrence Howard) and leaves a lasting impression. Telling a social worker that you’re basically a musical Jedi will do that, I guess. Unwilling to be placed with a family (because apparently he prefers to be bullied by the older orphans), Evan decides he’s had enough of this orphanage shit and takes off to New York City to find his lost parents through music. This premise is batshit crazy, but let’s plow ahead anyway. Evan, ever credulous, notices pint-sized busker Arthur (Leon Thomas III) and in short order finds himself swept up in a group of homeless kids squatting in a condemned old theater, where they learn about music from Wizard (the late Robin Williams), who basically pimps the kids as street performers. That night, Evan sneaks off with Wizard’s Gibson guitar and, having had no musical training whatsoever, begins to experiment—and finally, to improvise like there’s no tomorrow.

#NOPE

This gets Wizard’s attention, and instead of wailing on the boy for having purloined his guitar, which is what literature tells us should happen next, Wizard begins to favor Evan and attach himself emotionally to him, which is—lest anyone need a reminder—a classic child abuse tactic. Arthur, Wizard’s former star protégé, gets shafted in Wizard’s attention, because of course the black kid gets shafted. Realizing that Evan’s musical gifts far outstrip any of the other kids, Wizard hatches a scheme to get rich and christens Evan with his stage name, lifted from an advertisement plastered on the side of a delivery truck: August Rush.

Eventually—because you didn’t see this coming, right?—the cops raid the squatters. Evan (now August) takes off to the subway and ends up in what is presumably Harlem, where he is drawn into a church by the sound of a gospel choir. Noticed by the choir’s youngest member, a little girl named Hope (because of course her name is Hope), August learns to understand basic music notation, and practically in an instant begins cranking out page after page of musical ideas.

#NOPE

Not satisfied to putter around on some shitty old church piano, he ascends to the choir loft and proceeds to play the crap out of the pedal organ, having only discovered the concept of keyboard instruments like three hours earlier. Again: #NOPE.

Awed by this display, which literally culminates with the camera panning up the expanse of the organ loft until we see rays of sunlight beaming through the church windows and illuminating the cross perched on high, the church’s pastor brings August to Juilliard.

Before continuing, let’s take a moment to consider the messaging here of a poor little white boy who gets “saved” by a few black parishioners. The gospel music that sparks his initial interest comes replete with devices—bending of notes, speaking to gospel’s roots in blues-based music, and heavy embellishment—that have come to have significant influences on pop music, whose most successful stars have generally been white. Pointing the accusatory finger of cultural appropriation will, however, have to wait for another time, because this narcissistic train wreck of a movie isn’t over yet. We can’t know what August’s future relationship with this pastor and his daughter will look like, or whether he will help Arthur break free of Wizard and build his own life, but for the purposes of the movie it seems clear that black characters function to help white characters find their way. (There are also the scenes that make Mr. Jeffries arbiter of Lyla’s search for August.) But back to the “story.”

August soon makes waves at Juilliard where, suddenly empowered with musical literacy, he begins composing an orchestral rhapsody instead of doing his theory homework. I can’t say I blame him—but at least it’s tonal theory. It could be worse. (Serialism, anyone?) But also:

#NOPE

Called before Juilliard’s academic administration, which of course is a bunch of old white people sitting in a fancypants wood-paneled boardroom, August learns that the school has selected his composition for a premiere at one of the New York Philharmonic’s summer concerts in Central Park—the very same concert (gasp!) at which Lyla is to make her return to performing. Meanwhile, we see Louis (remember him?) wander from San Francisco to Chicago to New York in search of Lyla.

Things seem to go well until Wizard shows up in the middle of August’s rehearsal at Juilliard and coerces him to leave, because somehow in this movie August’s apparent musical savantism also means that he doesn’t have a backbone—at least, not until it’s the night of his debut concert with the Philharmonic. (Also, why doesn’t the Juilliard guy supervising the rehearsal, you know, call fucking security? Is he incapable of spotting a lie when he sees one?)

Back on his perch in Washington Square Park, August catches the eye of none other than his own goddamn father, Louis. Mutually oblivious to the significance of the other, the two play a totally improvised duet, of which we can say: #MOSTLYNOPE. Louis, who in all this apparently hasn’t the neural capacity to think, “Hey, this kid sure looks a fucking lot like me, and plays an awful fucking lot like me,” assures August that if he had such an important concert to attend, he would surely not miss it for anything. Wizard and Arthur show up, ready to take August back to his life of impending child abuse.

August announces he’s leaving Wizard’s pimping scheme behind and, with a little help from Arthur, escapes through the subway and makes his way to Central Park where—miraculously!—he arrives just in time to get outfitted in a miniature set of white tie and tails, have his hair coiffed, and be ready to conduct his rhapsody. Meanwhile, Terrence Howard’s Mr. Jeffries, who spends a lot of time being sad and astonishingly ineffectual, spots a bunch of spilled faxes on the floor of his office—faxes!—that bring him the revelation that Evan Taylor and August Rush are one and the same. He sets off for the concert, where he continues to be ineffectual for the remainder of the movie.

Lyla, drawn back to the concert by the realization that August Rush is her son, approaches the front of the audience in perfect parallel with Louis, who—despite having been in New York for God knows how long by now—has only just figured out that she must be at the concert, having been a featured soloist with the Philharmonic. They converge in the front row, where Louis takes her hand without so much as a word or tap on the shoulder. Wait, isn’t this actually an advance absent consent? Aren’t we in a moment now? WHAT THE AF IS HAPPENING???

Despite the fact that they are too emotionally dead inside to register anything, Louis and Lyla’s reunion reverberates a great disturbance in the Music-Force-Thing. August, his back turned to the audience, staggers under the effect of this mystical cosmic vibration. He turns around, knowing—without a shred of evidence—that these two people must absolutely be his parents. He beams, and . . . poof. That’s it. Fin.

#NOPE. SO MUCH #NOPE.

Dénouement? What dénouement?

Almost two hours of never-ending preposterousness and we can’t even get a joyous family hug? We can’t get some kind of cathartic emotional validation after all those slow-mo macro shots of people looking mopey or of instruments being played? After the vapid dialogue and the cheesy cinematography? After all the other #NOPE moments, too numerous to have included in this re-view?

Fuck you, August Rush. Fuck. You.

And now for a few words about the music in August Rush.

At this point in the re-view it’s perhaps unsurprising that, for a movie that’s practically masturbatory about the mystical significance of music, the score is nothing short of unadulterated nonsense from a composer, Mark Mancina (Speed, Twister), who should know better given the films he’s scored previously. If August Rush had been a different movie—that is to say, a good movie, with a good premise, a good screenplay, and a good director—we might have had a proper film score from a distinguished composer, the likes of Alan Silvestri, Howard Shore, or even my favorite late-career disappointment, John Williams.

After all, most movies aren’t about music, and I imagine that getting to score one that is about music is basically like getting asked to do your regular job and have your work get far more attention than it probably otherwise would. In theory, this should be a great honor, and you would expect a composer to rise to the occasion. It’s like getting to write a new version of Orfeo. In practice, however, Mancina cribbed everything from Van Morrison to Johann Sebastian Bach, producing nothing substantial or memorable in the process. Even the movie’s main melodic motif, the germ of what will eventually become August’s “rhapsody,” sounds curiously lifted from the “Promenade” theme from Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition.

This author notes with smug satisfaction that it all comes back to Bach. (It’s some of the first music we hear in the movie.) This author also notes that August Rush’s treatment of Bach makes him want to stuff a dirty sock in his mouth—to be washed down by a cup of bleach. I would, under other circumstances, probably not dismiss an arrangement of the Sinfonia from BWV 29, the cantata Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir. It is, after all, an arrangement by Bach himself—of one of the movements of BWV 1006, a partita for solo violin. Bach, ever a pragmatic recycler, raided the selfsame cantata for two movements of the B-Minor Mass, BWV 232. So it’s not the musical borrowing per se that irks me, or even the inept transcription for cello and orchestra; it’s the way that it’s shoved, like a puzzle piece whose protrusions don’t quite match the surrounding cutouts, into a soulless pastiche of “amorphous, pumped-up schlock” (from the New York Times review). And schlock it is, doing its schlocky duty to distract us from the crass religiosity and gross hypersentimentality that capitalism tends to trot out whenever it’s feeling guilty about how little it actually does to benefit the intellectual and creative enrichment of society.

It dumbfounds me that as a culture we should so widely and almost unthinkingly acknowledge the value of music and at the same time do such a shit job of providing music education in our schools and giving government support to the arts. We don’t take kindly to adults who read and write at an elementary level—we just elevate them to positions of incredible power, cough—but we’re totally fine with adults having a second-grade knowledge of music. August Rush is exactly the kind of “shameless hokum” (New York Times again), that I charge with indulging people in warm-n-fuzzy feels about the arts while simultaneously absolving them of the responsibility to support the arts in any material way. In fact, while it smothers us with All The Feels, it perpetuates exactly the kind of crap that’s detrimental to the way society approaches classical music.

Most obviously, the movie nakedly traffics in the fetishization of the musical prodigy. In some ways, I can’t blame it; as a culture we fixate on preternatural abilities of any kind in young people—music just happens to be one that’s easy to notice and promote. The sheet music store I patronize near Boston’s Symphony Hall shares a building with the administrative offices of From the Top, classical public radio’s premier venue for the showcasing of young classical whippersnappers. When your culture is obsessed with the 13-year-old who can play Brahms’ G-minor piano quartet—a real freak-show kind of act, if we’re being honest—you tend to leave less attention for the 43-year-old who isn’t a professional musician but really wants to learn to be a serious amateur. It’s an odd outlier in a culture that otherwise slavishly preaches the value of hard work leading to professional and personal success. It seems curious that we should apply this ethic to everything except the arts, where obviously it all boils down to some mystical notion of “talent,” rather than disciplined self-application just like everything else—a position that’s not only statistically more sound but which is also supported by recent research. Fetishizing the musical prodigy only serves to entrench the existing, misguided cultural message that music is only for the intrinsically talented.

Note too how the movie not so subtly sets up hierarchies of musical valuation. Jazz is nowhere to be found, as is non-Western music. Most references to “classical” music—mainly the Bach—almost immediately metamorphose into scoring with a decidedly pop slant, the main giveaways being the ceaseless uniformity of beats and the marked shift to shorter melodic units with simpler harmonies. Other cues signal the degree to which August Rush almost completely accepts the Stodgy Classical Music stereotype: in the beginning of the movie, for example, Lyla’s almost apologetically pleasant concert as contrasted with Louis’ energetic Irish rock concert, where people are waving their hands and dancing—and clearly having a lot more fun. Then of course we have the president of Juilliard, a humorless and buttoned-up woman who seems to have forgotten the passion that fires Juilliard’s students. She’s the epitome of stuffy elitism, a charge that many have leveled at classical music for decades. And lastly, we have Wizard’s rant in August’s rehearsal, wherein he all but accuses the school of smothering the boy’s musical creativity by teaching him “rules”—the fundamentals of tonal harmony, which underpin only about three centuries’ worth of Western music. I admit: I grew up with Western classical music and it holds a certain ineffable meaning to me, and I don’t get down with seeing it maligned just because it’s easy or fashionable to do so. (Somewhere in Berkeley, Richard Taruskin is preparing to smite me.) Ultimately, I just can’t get past these moments in August Rush, which, while not directly evocative of the #NOPE theme, are closely related to it. Moments like these made it impossible for me to spend any more time with this movie than I absolutely had to.

Normally for a 10YA re-view, I’d watch the film in question not once but several times, going back to certain scenes and scrutinizing the acting, the camerawork, the dialogue, or the music. But August Rush is such a train wreck, such a travesty of filmmaking, that I can’t imagine ever watching it again, in whole or in part. I despair to think that Actual People out there remember August Rush fondly (see the Free-Floating Thoughts, below). It’s a movie that makes me angry at not only the movie itself, but at myself as well, for having frittered away two hours of my life on it. But if by writing this re-view I’ve done the public a service, then it’s time well spent.

August Rush makes a compelling argument for a ban on movies about music, until filmmakers figure out how to make a movie about music that isn’t, you know, an epic insult. Sure, such a ban would violate the First Amendment, which, as conservatives never tire of teaching us, clearly states that a cake is just business—unless it’s for a gay couple’s nuptials, in which case it’s art. But I feel this deserves an exception.

I feel it in the water.

I feel it in my bones.

I smell it in the air.

. . .

#NOPE

Free-Floating Thoughts

– Apparently #augustrush is getting quite a lot of mentions on Twitter thanks to Highmore’s current role in ABC’s The Good Doctor. I don’t know what’s more horrifying—that people profess to love August Rush or that they apparently don’t realize that Highmore starred in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory in 2005 and gave a much better performance. I pity you, people of Twitter.

– August’s repeated assertions about the music he hears call to mind a wee Haley Joel Osment in M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense, tearfully confessing to Bruce Willis that he sees dead people. The difference, of course, is that the trio that anchored The Sixth Sense won widespread praise for their performances. The trio that anchors August Rush . . . not so much.

– I wrote in my re-view of Brokeback Mountain that I never really “got” the celebrity crush, but in re-viewing August Rush I’m reminded that were I ever to cross paths with Jonathan Rhys Meyers, I’d probably be in mortal danger of losing myself in those luminous aquamarine eyes—to say nothing of the great cheekbones and the mellifluously rounded accent. I’d like to think that somewhere in this godforsaken world, somebody else shares my pain that someone with such crystalline, azure eyes and such great cheekbones could be debased by the likes of August Rush.

– A friend of mine is a long-term sub with the New York Philharmonic. August Rush makes me want to ask her how the Philharmonic ever agreed to let its name be used in such a garbage movie.

– Some musicologists in recent years have taken umbrage at the Eurocentrism inherent in the phrase “classical music,” despite its being a relatively well-understood concept in Western culture. This charge has given rise to books like Michael Church’s edited volume The Other Classical Musics, which must surely be in contention for the Most Musicological Title award. It’s thus common now to qualify “classical music” with the “Western” modifier. Because that definitely solves the Institutional Challenges facing musicology in the twenty-first century.

– You would hardly know this movie is from 2007. Technology is almost conspicuously absent; it’s almost as if the internet doesn’t exist, save for a brief moment when Louis discovers Lyla’s identity on a web page that looks like it was created in 1995—the year that August, né Taylor, was born. Far too many people in this movie use pay phones, which speaks I think to the writers’ desire for a movie as saccharine as a Nicholas Sparks novel, because nothing inspires sentimentality quite like a bit of nostalgia. Most of the contributors here at 10YA were at least teenagers before cell phones came along, and even in our childhoods—or at least, in mine, I can’t recall using pay phones very much.

– This movie is fucking crazy. Fucking crazy awful.