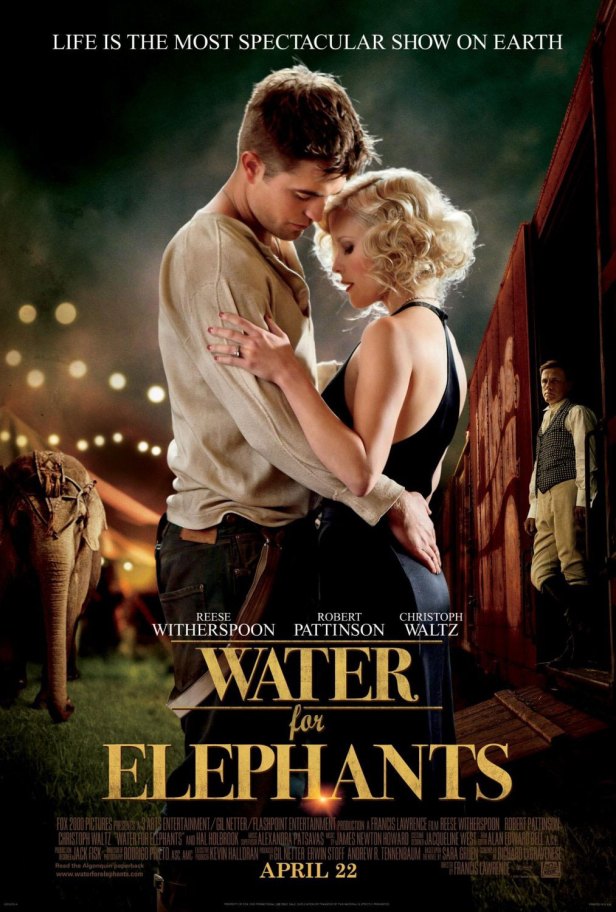

Dr. Stevi Costa does what she does best—talk about circuses—this time for the 2011 cinematic adaptation of Sara Gruen’s Water for Elephants.

I recently rediscovered Sara Gruen’s 2006 best-selling novel Water for Elephants when I was putting together an introductory literature class called “Stories & Circuses.” I hadn’t read the novel since 2006. I had barely even thought about it or the 2011 film adaptation until I added it to my syllabus in 2020. Part of the joy I find in teaching literature is the chance to read something again with fresh eyes, and so that was how I approached teaching a novel I didn’t even include in my PhD reading list. Or write about in my dissertation, which seems to me now an odd omission given that my research agenda could broadly fall under the course title “Stories & Circuses.”

Although I didn’t remember many details of the novel, its pachyderm heroine Rosie was the reason I wanted to include it in my course. Gruen writes animals so humanely, imbuing Rosie with such personality, animacy, and intelligence that made her an unforgettable aspect of this novel. I had a hunch that most of my students would immediately associate the idea of the circus with animals, given that they were raised amid the roar of a growing animal rights movement that had very recently resulted in barring the use of elephants in circus acts. I wanted this character to act as a window into discourses around animal-human relationships, environmental justice, and the function of displaying animals in performance contexts from a variety of perspectives. What I got out of teaching the novel again in 2020 was so much more. Water for Elephants is a good read, a richly historical novel that opens up discussions of gender, race, class, and ability during the Great Depression. We talked about the novel’s use of white ethnic particularity as a means of erasing racial difference, noting Gruen’s sly mentions of the black circus workers who “keep disappearing” whenever the show goes up in certain towns. We talked about informal economies and what kind of laborers they sustain and which they exploit. We talked about gender and power and choice and so much more because of this novel. As I argue most circus stories do, Water for Elephants uses the circus as a microcosm of the nation, one which is critical of capitalism while simultaneously being indebted to it. And even if you don’t care as much about circuses as I do, the novel’s narrative framework offers some lovely ideas about memory, nostalgia, and homecoming.

The film offers much less than the novel does. As an adaptation, it is relatively faithful. The script tightens the narrative on the central love triangle in which Cornell dropout-cum-circus veterinarian Jacob Jankowski and star equestrian rider of the Benzini Brothers Circus, Marlena Rosenbluth, must escape her abusive husband, August, the circus’s current “menagerie man.” Subplots from the novel involving a Dwarf clown’s search for belonging, an alcoholic roustabout’s loss of family, and a cooch dancer stirring Jacob’s nascent sexuality are all reduced to mere gestures in service of the main plot. In doing so, the circus loses much of its color and depth. Marlena’s backstory gets changed a tiny bit to give Reese Witherspoon a nice, wistful monologue. These changes work for the film, although I am fond of the subplots and do miss them. But I get it. It’s hard to capture every tiny detail of a 370-page novel in a film with a runtime of just over two hours.

The biggest change is the decision to collapse the characters of Uncle Al, the big boss owner of the Benzini Brothers Circus, and August into a single White Capitalist Patriarchy Boogeyman. I understand this choice, but in collapsing these characters, what is left lacks depth. Uncle Al is the capitalist who exploits his employees even after they’re dead and will throw any man who isn’t pulling his weight from the train in the dead of night. August isn’t so ruthless but is nonetheless an abuser. As an immigrant from a religious minority whose social position within the circus is equivalent to middle management, August has to prove his worth to Al. One might read his abuse of animals and his wife as an attempt to emulate the kind of masculine power that sits at the top of the hierarchy. My intention is not to defend an abusive man, but neither do I think the nuance Gruen lends to his character in the novel is intended to defend him. In fact, I think the Al of the novel is a critique of the very traits he embodies. This makes him a character, rather than a caricature. By collapsing August with Al, the screenplay loses this nuance and turns him into an easy villain. Christoph Waltz’s performance in the role chews right through this slim characterization, leaving us with an August that misses the point of Gruen’s work.

By and large, the adaptation works, but in shaving down the circus’s rough and complicated edges, the film glosses over the setting’s critical possibilities and packages it as PG-13 entertainment. This strikes me as odd because August himself has a line that is critical of the idea of a “family-friendly” circus; he claims Ringling reinvented the circus with “no sex, no grit,” implying that Benzini Brothers is a real circus, not a facsimile thereof. Yet Francis Lawrence’s film sands down the grit and removes the sex. Stripteaser Barbara’s role is significantly reduced. She is the first act that Jacob works for after earning a place in the show by shoveling shit, and he narrates that he felt he was changed as a person by watching her perform. (Later, she changes him further by deflowering him.) I am pro-Barbara not only because her inclusion as a character reminds us that burlesque and the circus went hand-in-hand well through the 1950s, when Ms. Rose Lee herself was touring in the cooch tent, but because she is also a full-service sex worker. Sex workers don’t often get to be included in narratives in ways that aren’t tragic. Throughout the novel, Barbara is just happily doing her job and I love Sara Gruen for choosing to represent her in that way. Barbara does, however, serve as a kind of foil to Marlena if you closely read the descriptions of their performances (and Marlena’s casual remarks about Barbara). Movie Barbara is reduced to her striptease act and a few appearances in crowd shots. She becomes a body, not a character. And what’s worse, we don’t even see her body. At the end of her strip, we only see her back as she twirls her tassels for the crowd. If I am supposed to believe that the Benzini Brothers circus has sex and grit, unlike Ringling Brothers, why am I denied the pleasure of watching Barbara do a job that she has consented to do? Why is Barbara being denied the pleasure of performing for us? Furthermore, all indications that Barbara offers other services beyond the stage are removed from the film as though they are unimportant. The reduction of her character and the cinematic choices used to present her to the viewer make Barbara unimportant, sweeping sex work under the rug in pursuit of a PG-13 rating.

The film has no problem with violence, though. It is willing to show August beat Marlena just as he beats Rosie with the bull hook. It is willing to show us Jacob and August getting into a fist fight. It is willing to show us the bodies of Walter and Camel strewn on the rocks after they’re thrown from the train. The adaptation offers us the grit but denies us the sex. The only sex that makes it to the screen is between Jacob and Marlena, preserving the love story. This choice seems consistent with a contemporary American understanding of what is morally acceptable for children to see and to learn (i.e. violence is unavoidable, but only have sex with someone you love and plan to marry).

The film overall seems to stand at odds with August’s critique of Ringling not only for these reasons, but also because it features close-up inserts of actual children enjoying the spec early in the film. The enjoyment on the children’s faces reinforces the wonder we are all supposed to feel when we enter the big top. In going to the circus, spectators are transported into a world of imagination and the human body put to extremes. Often, people say that going to the circus makes them feel like a child again as they are, for once, able to escape from the world as it is into an idealized fantasy of imagination. Francis Lawrence also chooses inserts of adults demonstrating this same enjoyment, but the inclusion of children is so striking because it shows that August’s own circus isn’t what he thinks it is. It is family-friendly. It is for children. And the film that Francis Lawrence has made of the Benzini Brothers Circus is likewise family-friendly—leaving just enough grit to provide authenticity but polished enough to remove things too adult for children.

One aspect of the novel that the film does maintain rather well is the focus on the circus as a laboring space. There are very few scenes of the characters performing for an audience, just as there are relatively few of these in the novel. (There are parallel scenes of Jacob watching Barbara for the first time, and watching Marlena for the first time, and a description of the first spec he sees, but little else.) Instead, we come to know the characters through their living conditions as they travel from place to place and through the work of their hands as they create an entire universe out of canvas, rope, and wood. I will never be anything less than wowed when I see a circus tent raised from the ground. It’s an image that lends itself well to cinema because, at a real-life circus, most spectators will never see this moment. They will walk inside the tent and be awed by the trapeze artists, the big cats, the clowns, and the equestrians, but they will never see the more invisible forms of labor that provided them the space in the first place.

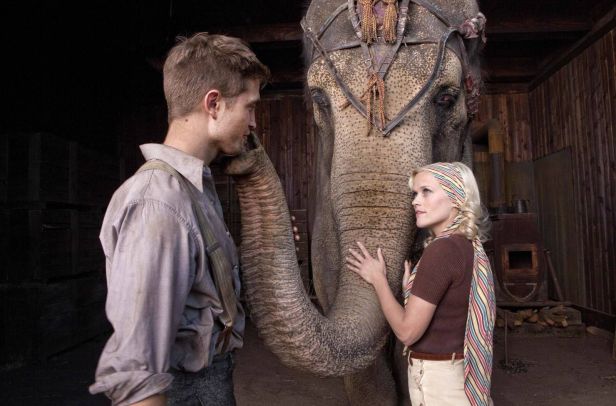

By taking this more behind-the-scenes approach, both the film and the novel show us the circus as a laboring space. This is particularly interesting with regard to Jacob’s work with animals and the development of his relationship with Rosie. To train an animal takes practice. And it is a relationship, as I have written about here. Jacob and Rosie evolve together as characters, both human and animal. They train each other, in a way, which is how performing animals should be treated. They are colleagues, not subordinates. And they consent to being trained. Jacob understands this, but August does not. He beats Rosie, rather than taking the time to understand how she works and what she is willing to do. We don’t get quite enough of the relationship between Rosie and Jacob in the film, which instead chooses to show us August’s brutality toward her to show us that Jacob is a good man and August a bad one. In this case, I think the novel wins out because it can offer a sense of interiority with animals that this film doesn’t quite capture. Without this, Rosie and Marlena’s relationship also falls flat, as does Jacob’s with Marlena.

The use of performing animals in the circus is hotly contested, with menagerie men and women fiercely defending their work and animal rights activists threatening to divorce them from the animals they’ve developed such intimate relationships with. I see far fewer arguments about the use of animals on film or in stage productions. I suppose these have better (but not perfect) labor conditions for both human and animal actors, but to me they are not wholly distinct in what they are asking of the animal performer. The animal performer must still be trained, must still work, must still travel to the job site, etc. The travel conditions for circus animals are perhaps less than ideal, especially for certain types of animals (like elephants), and it is this aspect and the way in which circus animals are trained that seem cause for concern.

There certainly has been documented abuse of circus animals. Ringling Bros in particular has been accused of abusing its elephants in a suit brought before the Supreme Court in 2000 by the ASPCA and former Ringling menagerie man Tom Rider. One interesting detail of the case was Rider’s claim that the abuses he witnessed of elephants while working with Ringling caused him emotional harm that made it impossible for him to work with animals again. Rider’s claim of PTSD hinges on the same human-animal connection that the book makes between Marlena and Rosie—a connection that is all but lost in the cinematic adaptation. In the book, our first narrative of the stampede makes the reader think that Marlena killed her husband with Rosie’s spike. Only later when we see the story told again through young Jacob’s eyes (rather than older Jacob’s failing memory) do we realize that Rosie freed herself from her abuser all along using the tool of her own oppression. ASPCA vs. Ringling Bros was ultimately dismissed in 2009 because the court found it specious that Rider did eventually go back to working with animals, thus damaging his claim of PTSD. The case is obviously a mess in terms of its understanding of disability, and its seeming failure to understand how hard it must have been for a man like Rider who truly loved animals to not feel comfortable around them because of sustained abuse, let alone the abuse the animals suffered. But, as I alluded to earlier, there was still a victory here: in 2016, Ringling Bros abandoned the use of elephants in its circuses. A 2011 expose in Mother Jones magazine brought the very allegations Rider and the ASPCA had pushed to the Supreme Court into clear public view. Shortly thereafter, Ringling was found to be in violation of the 1973 Endangered Species Act due to its treatment of elephants. In 2017, Ringling Bros filed for bankruptcy and subsequently took its final bow. In part, this was the result of continually flagging sales for American-style traveling circuses. But I’m sure it also had a lot to do with the staggering damages the company was ordered to pay after the Mother Jones expose came out.

I do not believe animal performance is inherently exploitative, but I agree that the time of circus elephants should have been over long ago. In the 19th century, and even in the early 20th century when the circus was still at its zenith, most Americans wouldn’t have the opportunity to see an elephant up close. If there was a zoo in their city, they surely would be able to encounter these beautiful giants on more consistent basis. Zoological gardens (like museums, another 19th century invention) brought nature to people in ways that promoted education and, eventually, conservation. Neither of these were the goals of the circus, but if you lived in rural America and had neither zoos nor museums nearby, the circus made wild animals accessible to human beings. A circus elephant was a big draw because it offered an opportunity for new knowledge, for wonder. To ask that elephant to perform only increased its value. But in an increasingly smaller world where seeing an endangered animal is as easy as Googling an image or watching a nature documentary on Netflix, perhaps our close-up educational encounters with endangered species should only be in education and conservation spaces, like zoos. (Or, better yet, wild animal parks.) The circus elephant has served its purpose. But because the elephant and the circus seem so inseparable in the cultural imagination, the loss of the circus elephant has ultimately signaled the death knell for the American circus.

Perhaps it is for the best that Ringling Bros Barnum & Bailey, the biggest name in the big top, has finally gone belly-up. Circuses are a fundamentally capitalist enterprise, yet they offer the public a temporary escape from the pressures of daily life under capitalism. They are full of contradictions like this, as is the country that birthed this particular style of circus arts. Men like Barnum made their names on the backs of hundreds and thousands of working men and women, using up the laboring capacity of their bodies and offering them very little in return. Yet stories about circuses (and stories from circus performers) are also stories about found family, about freedom, about choice and consent. Where else would a vet school dropout fall in love with an equestrian rider and an elephant? Where else would a Dwarf who reads Shakespeare befriend an aging roustabout? When abandoned by your biological family, where else can you make one out of humans, animals, and a canvas tent? As I watch the fairground circus of yesteryear dwindle in favor of European circus models that serve up a mix of aerial acts and clowning (a la Cirque du Soleil, which has its own money issues to worry about), I wonder if my students will only over see circuses represented on film in this way, with their edges sanded down, their capacity to create wonder reduced.

In 2018, I presented some of my dissertation work at the Circus & Its Others conference in Prague, which was conveniently scheduled during the World Circus Festival. Letna Park became a giant fairground with dozens of circus tents propped up all over its east side, each one offering three shows a day from a variety of different European circus companies. I only saw two shows there, but they were both wonderful inventions on the form. Prague’s Brothers Tricky created a spectacular narrative juggling showcase set at a funeral that delighted me from end to end. But Baro d’Evel’s Bestias was something else altogether. It is a performance that makes a case for more animals in the circus, not fewer. The company contained eight humans, two horses, and four birds. The show was presented in five different languages, switching between French, English, Czech, Italian, and Spanish. Rarely were any humans speaking the same language at the same time. Sometimes clicks and bird sounds replaced human language entirely.

I cannot accurately describe the entire performance, nor can I say I fully understood it. But I think the work that Baro d’Evel does with performing animals speaks to the necessity of cultivating a relationship between the human and the animal and completely reinvents the “circus animal” in ways that rewrite the traditional narratives of training-as-dominance. In Bestias, the human performers are attempting to convince the animals to do things, but it is 100% up to the animal to respond. The human must then improvise their performance around what the animal has chosen to do. For example, a woman danced with a trio of birds, trying to convince them to fly between her hands and her feet. She vocalized to them throughout, egging them on. Sometimes they just sat on her arms and did nothing. If they didn’t feel like flying, she simply made comedy out of it. The troupe’s master equestrian performed with two horses, singing to them as if to lull them to rest. They would lie on the floor and roll around with her. She carried a crop, but rarely used it, tapping them behind the knees only when necessary. At one point during the performance we saw, one of her horses just ran offstage, leaving her to perform the act with one fewer dance partner. The show went on. Bestias is a mesmerizing meditation on communication and connection between the human and the animal. It’s multilingual, polyvocalic nature made the audience feel the way animals must feel when we try to train them. Some audience members likely understood nothing that was said, some of them perhaps had a language or two worth of understanding. No one understood everything (unless they spoke bird). In the 21st century, this is the kind of illumination the animal circus should offer. It was more than enough in the 19th century for us to wonder at the mere sight of an elephant, but now the presence of animals at a circus must prompt us to look inward and wonder about ourselves.

A Footnote

If you haven’t read the Vulture piece on Sara Gruen’s fight for her prison pen pal’s appeal and her subsequent descent into chronic illness and near financial ruin, please go read it now. It is the circus novel crime story I didn’t know I needed.

— Stevi Costa