Erik Jaccard revisits Roland Emmerich’s The Day After Tomorrow and explains not just why this climate change narrative validates neo-liberal selfhood, but why we like disaster porn so damn much.

The Day After Tomorrow (Dir. Roland Emmerich)

Let me get something out of the way: The Day After Tomorrow is a very, very bad film. It was bad in 2004 and it is bad now. I find little in the film to redeem it after all this time other than the fact that, as I explain below, the subject which drives it—global climate change—has only become more serious while out attitudes remain equally as cavalier. I say this knowing that I did, in certain ways, still enjoy it for all its terrible writing, acting, and, oh everything else in 2004. But for the reasons I enjoyed it—and the new reasons I feel bad about that earlier enjoyment—you’ll have to read on.

Taking on the Good Ol’ Boys

Parts of The Day After Tomorrow are extremely dated, if otherwise good for an occasional chuckle. Released at height of the 2004 presidential election campaign season, it clearly wants to take pot shots at the colossal arrogance and myopia of the cronyist Bush administration’s ongoing assault on environmentally-minded federal policy. Admittedly, there is much to applaud about this. Under Bush, the US took dramatic steps backward in the public recognition of human influence on the natural world, famously backing out of the 1995 Kyoto Accord, caving at the drop of a hat to the coal, oil, and gas industries, and disseminating a surprisingly hefty amount of disinformation about climate change. In addition, the administration was accused of, among other things, purposefully censoring scientific data demonstrating the accelerated pace of global warming trends, and of doctoring testimony in federal courts which would have led to more stringent regulations on vehicle emissions. The reason for most of this politically-motivated obstructionism was clear throughout—‘cost.’ As in, the ‘cost’ to business, jobs, profit, and even to the ‘American way of life,’ which we all know demands that we all drive forty miles to stuff our faces at Chili’s before heading to the mall to fill five plastic bags full of stuff we probably don’t need. Because growth. Because GDP. Because, as Huxley’s Great World Controller, Mustapha Mond, once said, “The machine turns, turns, and must keep on turning—forever. It is death if it stands still…Stability…The primal and the ultimate need. Stability. Hence all this.” As we all know, one of the most maddening things about Bush Administration political strategy was the tendency to entirely ignore things that fell outside its very limited perspective on what the world was and how it should be run (and who should run it). If it didn’t matter, it was almost as if it didn’t exist. And if one did have to address it, one could always resort to the standard Reaganomic playbook and repeat the tired old adages about cost.

‘Cost’ is, of course, the exact same reason offered by The Day After Tomorrow’s Dick Cheney look-a-like Vice President when he is pressed to ‘do something’ about climate change by Dennis Quaid’s dire-faced scientist (one wonders what could actually be done in an alternate universe where the global climate can shift dramatically in a week). I’d forgotten until this re-viewing how weird it was at first that the film’s central political figurehead was the American Vice President, and that the Big Kahuna Burger-in-chief himself spends most of the film looking confused, simpering to the Veep and a coterie of experts for advice. And then I was like, ‘oh yeah,’ Dick Cheney, Daddy Bush’s puppet master, and little George W, the frightened child. For better or worse, the film promotes a somewhat immature schadenfreude, clearly targeted at those of us who were around in 2004, bleeding blue with the embattled Dems and licking our wounds as the machine rolled over us and into foreign lands. For example, it’s no mistake that the President bravely (some might say stupidly) goes down with the Polar Express of Doom, leaving the savvy, arrogant Veep to tuck tail and flee to Mexico, where he is ultimately forced to admit the error of his moneygrubbing ways and issue a plea for amnesty to the inhabitants of the Global South, which he has heretofore treated with glowering disdain. Indeed, the film’s denouement manages to prepackage a perfect political outcome for Bush naysayers: the charismatic cowboy figurehead is dispatched, his ventriloquist is compelled to emerge from the shadows to receive his comeuppance, and best of all—WE WERE RIGHT, YOU SILLY FOOLS. Oh, the hubris.

I’d argue that in 2004 this gleeful burst of righteous triumphalism from the liberal left (righteous even in catastrophe) meant something different than it would today. Back then successes for the left, environmental or otherwise, often had to be projected into the realm of culture, where fantastic resolutions to current problems could be rehearsed as a kind of joyous wish-fulfillment, a last-gasp attempt to ratify the victorious gains of the past by once again reminding a world that seemed no longer to care of their value. I once read a very smart review of David O. Russell’s I ♥ Huckabees (also 2004—head back here in October for the re-view) which interpreted its central dilemma in the same terms, claiming that it dramatized the left as essentially having a conversation with itself, asking how relevant it still was in a world where the George W. Bushes of the world could act recklessly and with impunity. While you probably never thought there was much in common between Day After Tomorrow and Huckabees, it’s hard to deny that both films gravitate around a solipsistic liberal pole of well-intentioned world changers wondering why they no longer matter. Both films also essentially retreat from this dilemma into a fantasy space in which their most pressing problems can be displaced and reinterpreted as other, less immediate problems. For Huckabees the displacement is from politics to ontology, or, more accurately, from a disagreeable reality to a more enlightened existential perspective (It’s ok if the smarmy Target executive is going to pave over your favorite wetlands; just hit yourself in the face with a ball and experience pure consciousness!). In The Day After Tomorrow it’s from political praxis to disaster-as-politics (If you can’t do anything right now, just project your disappointment outward into the future, where nature will do your fighting for you. And anyone, there’s no reason to actually worry, as this is all bullshit science. Keep shopping!).

Look, ma, it’s snowing!

Given the amount of attention devoted to global warming in the media, few would have known in 2004 that the central premise of The Day After Tomorrow, that the earth could be suddenly thrust into a new ice age, is not a new one in the history of either science or catastrophe narrative. For example, scientists have known for quite some time that natural variations in solar radiation have the power to shift terrestrial climate significantly, and these risks have often prompted them to warn of the potential for ‘little ice ages’ in our future. For us mere mortals, this is an easy enough possibility to bear because there’s little that could be done about it. It’s kind of like a meteor strike or that supervolcano under Yellowstone National Park suddenly erupting. Of course, it hasn’t stopped us from exploring the dramatic potential in natural catastrophe that has so captivated people in the modern West (for more on catastrophe narrative, see my June 2013 re-view of 28 Days Later. In fact, the first to explore the scenario was the English sf writer John Christopher, whose 1962 novel The World in Winter has the earth fall back into a new ice age because of abnormally low solar output. Maggie Gee’s 1998 novel The Ice People takes a different direction with the same premise, even going so far as to preface its main narrative with a collection of paranarrative excerpts from real paleoclimatalogical research, all of which points to the likelihood of a resurgent glacial period.

What bothered me about The Day After Tomorrow in 2004, and what still bothers me today, is the idea that the film exploits this technically possible outcome by shifting the conditions under which it occurs and then attributing them to human intervention. This has the effect of relativizing the seriousness of the latter issue while exploiting the shock-effect of the former. For those who have not seen it (or have not seen it for ten years), here’s a refresher on the ‘science’ of the film. As we all know by now, the excessive use of fossil fuels leads to an excess of heat-trapping greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere, which then cause the global temperature to rise. As most credible scientists now agree, while such fluctuations occur naturally, humans have had a discernible effect on the rapidity with which this process is proceeding. Rising temperatures cause not only drastic shifts in global weather patterns (hot air makes the weather all crazy), but also the significant melting of ice at the poles. So far, we’ve mostly been rightfully concerned about rising sea levels and the effect they’ll have on low-lying population centers. So far, so good. In The Day After Tomorrow, however, all the fresh water melting at the poles tips the salinization balance of the earth’s oceans, causing the North Atlantic Current (closely attached to the Gulf Stream) to stop warming the northern hemisphere’s climate. While the most likely cause of a new ice age—solar output—is actually referenced (and dismissed) in the film, what actually happens is that the NAC comes to a halt in a matter of days and transforms the earth nearly overnight. As some scientists agree, the film’s depiction of this climate chaos is a decidedly mixed bag. On the one hand, it acknowledges the effects of human activity on global climate shifts—something of a pariah subject during the Bush years (see below). At the same time, it shifts the frame of reference (for dramatic effect) such that the very subject of human intervention becomes patently ridiculous, a fun simulated effect that need only trouble us for the duration of the film (because really, how could the earth’s climate change in a week?!?). In other words, the film exploits a premise that is deadly serious for the purpose of allowing moviegoers to watch half of the earth topple. In Emmerich’s 2012, this was, again, much easier to stomach, because really, what are you going to do about Mayan religion? (Whoops, guess we should have paid more attention to that priest!) The Day After Tomorrow, sadly, is about something we can change, and it turns that potential into a spectacular joke.

The Dangers of Disaster Porn

‘Disaster Porn’ is a lexical hallmark of the new millennium, a phrase we were forced to invent to describe the seamless synergy in visual media between civilizational anxiety, first-world arrogance, the mass commodification of sexuality, and contemporary consumer society’s driving ethos of instant gratification. As far as I can tell, in its short history it has accumulated a few different meanings, depending on who you’re talking to. I want to deal with two here. First, Taryn O’Neill claims it was coined collectively, albeit interdependently, by a trio of Hollywood execs (Zach Stentz, Warren Ellis, and Damon Lindelof) in relation to the increasingly gruesome and technologically epic depictions of both natural and man-made catastrophes in film and television. At the same time, ‘disaster porn’ has also been used to describe the interplay between mass entertainment and real-world catastrophe, with the purpose of shining a light on how the 24-hour infocycles of contemporary mass media fuel the collective desire of so-called First World viewers for cataclysm and misery. ‘Desire’ is an important and often-neglected word here, as the reason we call this disaster porn is because the logic behind it mimics the logic inhering in the conventional relationship between a voyeur and the sexually stimulating images they consume for pleasure. To my mind, melding these two definitions allows us to question how the disasters we dream up and consume in our popular imagination are connected with the ones we watch play out on TV as ‘real’ news.

The Day After Tomorrow is like porn from the 1970s: it forces us to sit through a variety of ‘real’ cardboard storytelling while all we really want to do is see the next major disaster or epically surreal shot, whether that be a tornado taking out the Hollywood sign, a tidal wave rolling slowly into NYC. These aspects are the disaster film’s equivalent of the traditional porn ‘money shot.’ The product of increasingly fraught tension, they finish us off with a cathartic climax, after which we can only shudder at the ensuing carnage and recharge as we await the next build-up and finish (if it sounds like I’m viewing all this from a male perspective, I am, because porn is predominately created in relation to the male gaze and sexual climax and because, like most media, disaster porn mimics this relationship with its audience, no matter how many women are in it). So we wait. We wait through the insufferable father-son conflict between Dennis Quaid’s righteously vindicated paleoclimatologist, Jack, and his smarter-than-he’s-given-credit-for son, played by Jake Gyllenhaal. We wait through the dramatic tension of deciding whether to take Jack’s dire prognostications seriously and through the remorseful realization that he’s been right all along. We wait while the cast sleepwalks through its lines and while the film sleepwalks through its plot, all the while knowing that we’re each a furtive set of hungry eyes and ready hands in front of a yawning computer screen. And then we get our fix, settle down, and wait for more, growing entirely dependent on the promise of the next disaster (or fight scene or car chase or, or or…) to really blow our minds. Until one day we find ourselves sitting down to a disaster flick unconsciously waiting for the equivalent of what Matt Stone and Trey Parker once called the ‘DVDA’ (I’ll let you look that one up yourself), the most extreme thing we can think of without resorting to the instantaneous destruction of the entire planet. (Sorry Alderaan, but where’s the titillation in that?) And we watch and get off, safe in the knowledge that nothing is real, that we’re cozily nested in our couch or theater seat. Safe with a little innocent fun.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m just like you. I fucking love watching things get demolished in this way. I won’t pretend I’m not just as addicted. There’s a very visceral sublimity in the sight of New York inundated by a giant wave or downtown LA destroyed by massive tornados. It’s difficult not to watch something so immense and mysterious and terrible without feeling a certain rush of excitement and energy, a thrill all the more thrilling for the fact that the viewing experience remains safely insulated from any actual danger. We live humdrum lives. We work, we talk, we pack our lunches, we play with our kids and walk our dogs. Indeed, part of the rush supplied by disaster porn is in forgetting the safety of our structured, heavily administered lives. Just like traditional pornography, disaster porn is a fantasy that we use for our own ends, and that puts us to use in the generation of revenue. This is, of course, one of the reasons we keep making them and paying to see them. It’s why we rank disaster porn films in relation to one other, carefully evaluating which give us the biggest and most intense thrills and which fall short (visit any one of the myriad free porn sites available online and you’ll see that they also allow viewers to select a ‘score’ for individual videos and, of course, discuss why each video is worthy or unworthy of viewing). We also do this with roller coasters, rock climbing, and any other physical or mental activity meant to give us a taste of danger and make us feel ‘alive.’

Maybe you see the problem coming. The problem is that the thrills of disaster porn are all too readily merged, via the way we experience the ‘reality’ of world events through mass media, with real-life tragedy. Which is why the phrase bursts into existence nearly simultaneously as a response to increasingly violent films and as an analytical concept created to describe audience relationships to tragedies such as 9/11 (2001), the Southeast Asian Tsunami (2004), Hurricane Katrina (2005), and the Haitian Earthquake (2010). The rise of the 24-hour news cycle ensures us that we can watch an uninterrupted stream of carnage from the safety of our living room, equally as insulated from any troubling implications. Two of these massive cataclysms have already been dramatized in Hollywood Films (World Trade Center (2006), and The Impossible (2012)); the other two are likely too sensitive politically to touch yet. Even these two could likely only be made by transforming the carnage into a story about the tenacity of the human spirit. This spirit is real, valuable, and worth dramatizing even if only we have so many instances of human wickedness with which to oppose it. But it’s also a safety valve or red herring that allows us to get our fix without feeling too bad about the real subject at the bottom of the misery. This is why neither Katrina nor the Haitian disaster make for good disaster film material—they both uncomfortably remind us that the reason people suffered was not just because nature is wild and unpredictable—“red in tooth and claw,” as Tennyson put it—but because some are structurally locked into social and political conditions in which they were (and are, every day) more likely to die. Dramatizing either of these events entails entering sobering territory that leaves would-be disaster film devotees, insulated behind their TV screens, too vulnerable to criticism and moral ambiguity.

You might be asking what this all has to do with The Day After Tomorrow? Clearly, it does not dramatize any real-world catastrophe, nor does it really attempt to lure us in to its entertaining scenario with anything but the flimsiest of scientific pretenses (see above). So why worry, right? Here’s the thing: disaster porn like The Day After Tomorrow (and it isdisaster porn, just as Roland Emmerich is a disaster pornographer) models and encourages our detachment from a world of real, dire, scary problems, just as hyper sexualized porn models our detachment from sexuality and intimacy. It rehearses an old and extremely problematic relationship between human beings and nature as a relationship between subjects and things (much like most porn). Just as it’s very difficult to see your partner clearly as a person if you mediate your sexual relationship with him/her through grotesquely exaggerated fantasies, so, too, is it extremely hard to maintain a healthy relationship with the world of which you are only a part if your relation to that world is mediated through violence and cathartic climaxes. Not only does this reduce nature to only one its functions (it also creates, you know), it also legitimizes the ongoing ‘taming’ of nature, by humans, for reasons that are all to do with creating and maintaining human power over things (again, like porn). And all this from a film that, by most respects, says and does all the right things when it comes to human influence on the natural world.

This is The Day After Tomorrow’s most enduring legacy ten years on from 2004, and it almost makes me mad to say that it’s equally as terrible now as it was then, but that it has also become a more important film because its subject matter is even more dire now than it was 10 years ago. As we all know, things have only gotten worse since 2004, and very little has gotten better. The glaciers are still melting, the ground is still being poisoned and destabilized, and what gains we make always seem like a speck on an otherwise festering sore. We’ve reached a point at which not doing anything will likely have serious, possibly catastrophic consequences. We need action, and what we have is dozens up dozens more disaster porn movies, films that increase, rather than mitigate, our passivity.

Free-Floating Thoughts

- Man, Jack really wants to save those ice core samples. If it weren’t for Hollywood theatrics and the kind of athletic ability that occurs about as frequently as Halley’s Comet, he would not make that jump, samples in tow.

- Speaking of impossible physical feats, in this alternate universe one can literally outrun the forces of nature while dragging an injured comrade. Clearly this is symbolic of Jake Gyllenhaal’s courage, fortitude, and colossal quad strength.

- Ha! The President’s final address is being carried by the Weather Channel!?! Because all the other networks were somehow obliterated in the cataclysmic climate carnage. [Side Note: the Weather Channel’s US HQ is actually in Atlanta, so maybe there is some truth to this seeming absurdity]

- For some reason I can’t comprehend, I love the actor Jay O. Sanders. He’s among my favorite ‘Middle Initial’ part-actors, right up there with Craig T. Nelson.

- I’m also a fan of Dash Mihok. One day I want to meet his kids: Son, Colon and daughter, Hyphen.

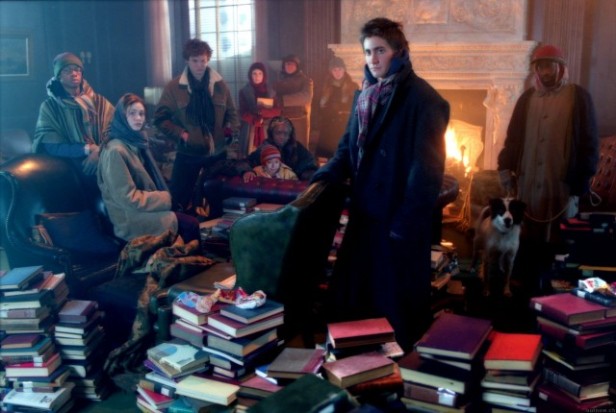

- Nature is very uneven, windy, unpredictable, yes? Most post-1800 Euro-American designs are not. Instead, they tend to be rational, orderly, you know, of the desire to tame nature’s unpredictable ways. So let’s talk about how a giant tanker gets from the Atlantic Ocean, via lower Manhattan, to just outside the New York Public Library, where it can be glimpsed in all its sublime glory by a bunch of tenacious survivors hiding out there. First, it would naturally enter the city through the inundated Battery District, full of who knows how much water. As the film makes it seem, enough so that a tanker with a significant amount of submerged displacement could eke its way through the city a few feet off street level. Then, it would proceed up Broadway before making a hard right onto Canal Street, where it would have to travel another eight blocks before taking an equally as hard left onto Bowery. Bowery offers a nice, wide pathway up until it hits a T junction at Union Square. I’m guessing the pilotless tanker (captained only by the whimsy of that unpredictable force we call nature!) would avoid the hard left onto W 14th St. and instead make the easy right onto Park Avenue, which would afford it another long, wide thoroughfare on which to drift until it reached the hard left onto W 40th St. Having made that perilous turn it would continue for another breezy two blocks before it arrived at its destination—the New York Public Library—at 455 5th Avenue, New York, NY 10018. Logic be dammed, there’s a tanker in the middle of downtown New York! CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?!?!

- “Sam, just tell ‘er how you feel.” “Thanks, hunky prep school guy, but I’m Jake Gyllenhaal. I got this.”

- There’s a scene with Ian Holm and his forsaken cadre of climatologists hunkered down in their Scottish research station where one, trying to help out, asks aloud whether the generator—about to run out of fuel—might run on the remaining contents of a bottle of 12 year-old Balvenie, a fairly well-known single malt Scotch Whisky. “Are you mad?,” Holm replies, “That’s a 12 year-old Scotch!” As though it were a Balvenie 25 year-old, cask-aged, cherry-hinted dram of ambrosia.

- Sela Ward’s job in this movie is to make ‘mother hen’ face and ‘pained’ face. That’s it.

- Jake Gyllenhaal, 22-23 years-old at the time of filming, looks about 22-23 years-old at the time of filming. But hey, he’s got a boyish face. Beverly Hills 90210 casting strikes again!

- Ok, I get that the only way to get wolves to act like the Raptors from Jurassic Park is to create them digitally. But these wolves are comically aggressive and angry from the very get go, chomping at the bit to get out of their cage as the chaos descends on NYC. The feeling I’m guessing we’re supposed to take away from the scene of their empty cage is about the same as the feeling we get in—you guessed it, Jurassic Park—when we find the raptors are on the loose. Except that these are wolves, not raptors. They’ve been in captivity for God knows how long and are probably accustomed to three squares a day and a zoologist named Burt attending to their every captive need. But no, what we’re meant to take away from the entire wolf-fiasco in this film is that wolves are naturally, genetically nasty, and a viable natural competitor to humans in this post-catastrophic ice world. As Alpha Wolf—I’m going to name him Vrog—might say: We’re coming to fuck you up, humans! Your infected wounds smell like victory! Owoooooooooooooo!

- Oh, the surrealism of the Planet of the Apes/Statue of Liberty shot, but with snow!

- The sea was angry that day my friends. Like an old man trying to send back soup in a deli. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0u8KUgUqprw)

- Massive tornados disrupt potential nookie and flatten TV weathermen! By the way, if you’re trying to have sex, you die! The rules of horror film are always in play.

- Street prognosticator/homeless guy with dog, telling it like it is because he lives on the outside of the garish consumption which fuels its vicious spiral of opulence and waste. To my mind he’s playing a less funny version of Eddie Griffin’s character inArmageddon.