Brian Malone returns to Ten Years Ago with his re-view of Spirited Away, a half-remembered dream of a film that hinges on acts of reconciliation and the logic of the uncanny.

Spirited Away is the third film by Hayao Miyazaki that I ever saw—and the first that I liked. I came to Miyazaki through peer pressure. I’m not an animation buff, so it took the repeated urgings of my more anime-inclined friends to get me to watch Miyazaki. I started with Kiki’s Delivery Service, but I found it a bit silly and much too cute (and the English-language version involved more Kirsten Dunst than I am willing to tolerate). Then I watched Princess Mononoke, which I found way too brutal. Finally, just as I was ready to give up on Miyazaki, I came to Spirited Away and was entranced. It was beautiful and complex and strange without being alienating. In other words, it was just what I was looking for. And while I would eventually see (and enjoy) several more Miyazaki films (including the delightful My Neighbor Totoro), Spirited Away has remained my favorite.

So naturally, whenever Miyazaki comes up in conversation, I always mention how much I love Spirited Away. And yet, several years ago I realized that as much as I profess to love that movie, I actually didn’t remember much about it. Over the years, the film had been reduced in my head to a few basic plot points and some image fragments. I remember that it’s about a young girl who is trapped in a bathhouse. I remember that her parents are transformed into pigs. I remember a strange masked ghost with an insatiable appetite. And I have a vague recollection of animate sootballs. But this amnesia is a little puzzling. These few tidbits hardly seem like enough, especially considering that I can replay full Pixar films in my head and perform entire musical numbers from the best animated Disney musicals.

So naturally, I jumped at the chance to re-view this film. It would be an opportunity to remind myself not only why I love Spirited Away, but also what it’s actually about. And when I watched it again last weekend, it became clear to me why I found the film so difficult to remember during the last decade. Spirited Away is hard to remember because, compared to standard American animated films, it just doesn’t make sense—at least, not quite in the way you expect it to.

Before I explain what I mean by this, let me try to summarize the plot. The film is the story of ten-year-old Chihiro, who is moving with her parents to a new town. She is not happy about this. She’s sad to have left her friends and she’s not excited about attending a new school. On the way to the new house, Chihiro’s father (driving an Audi, as my car-obsessed partner helpfully pointed out) takes a wrong turn and they end up at an abandoned amusement park. Once inside, her parents follow a delicious smell and come upon a sumptuous buffet in an apparently abandoned restaurant. They begin to eat ravenously and suddenly change into pigs.

At this point, things get weird. The sun starts to set and spirits begin to appear. Chihiro stumbles upon a giant bathhouse with a smokestack. She meets a boy named Haku who tries to help her escape, but the sun sets before she can make it to the gate. Trapped in this world, Haku sneaks her into the bathhouse and convinces her that to remain human she must get a job. The bathhouse is run by an old witch, Yubaba, who reluctantly agrees to hire Chihiro (but steals her name). Haku explains that the only way to eventually escape is to remember her real name and to be able to identify which pigs are actually her parents. This is Chihiro’s task.

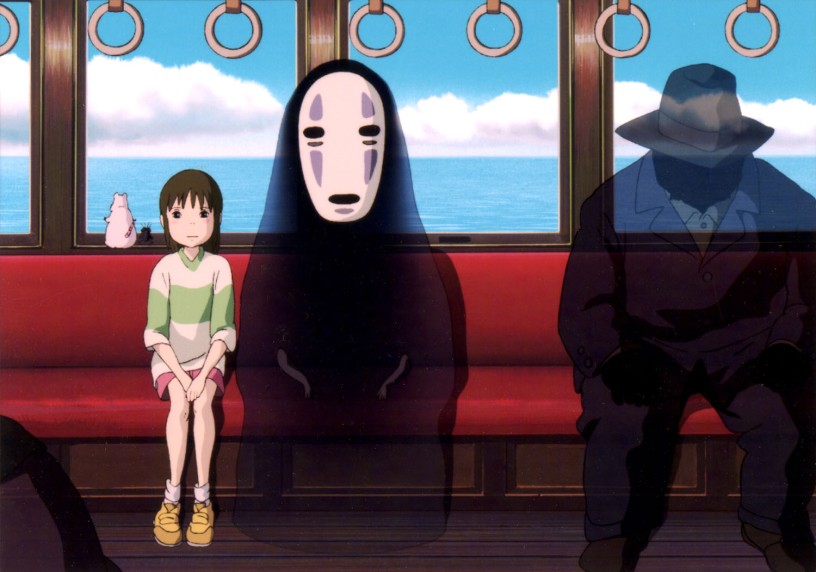

But it’s not that simple, of course. From here on out, there is probably no way to summarize the plot without resorting to a series of bizarre and seemingly unconnected declarative sentences. Haku turns out to be a dragon who is enslaved by Yubaba. Chihiro bathes a polluted river spirit and is rewarded for her compassion with a bolus of medicine. Haku is mortally wounded by a flock of paper birds sent by Yubaba’s identical twin sister Zeniba, who is angry that Haku has stolen her golden seal. Chihiro lets into the bathhouse an initially mute spirit named No Face who begins to eat everything and everyone in sight until Chihiro purges him with her medicine. Haku is healed by Chihiro’s love. Chihiro and No Face journey—through a shallow lake, by train—to Zeniba’s home to apologize for Haku’s theft. Chihiro frees Haku from Yubaba’s curse. Zeniba gives Chihiro an enchanted ponytail holder. When she returns to the bathhouse, Chihiro must pass one final test from Yubaba before she is allowed to collect her parents and to return to her world. Yeah, it’s that kind of movie.

How do you make sense of this? Is there a Western antecedent for this kind of narrative? At first,The Wizard of Oz came to mind. However, I would argue that Spirited Away is much stranger and, ultimately, less reassuring. The land of Oz is bizarre, but it’s also just a slightly skewed version of Dorothy’s own everyday life (the same characters recur in different incarnations). And that’s actually the point of Oz. It’s intended to teach Dorothy a lesson about how much she actually does love her life in Kansas. In contrast, the moral of Miyazaki’s film is murkier, although I would argue that it is definitely not “there’s no place like home” (more on this later).

A better narrative precursor to Spirited Away is probably Alice in Wonderland (the book, not the execrable Tim Burton movie). What is similar about the narratives in Alice and Spirited Away is that they do not really depend on a standard quest story. In order for Dorothy to get home, she must go on a quest for the Wizard (and then, to defeat the Wicked Witch). Alice, on the other hand, isn’t really on a quest (except in that terrible Tim Burton film). She’s just bouncing from one strange situation to another and having an occasional cup of tea while doing it. And while Chihiro wants to get home, it’s not really clear at any point in the film what she needs to do to get there. She just putters around, does some good deeds, has some adventures, and somehow muddles through it all. Both of these narratives refuse to provide a clear climax point (and that’s presumably why Tim Burton felt he had to add one in his dreadful Alice film). In other words, neither of these stories is building to one moment (e.g., the melting of the Wicked Witch) in which everything is suddenly resolved. There is no one climactic action that defines the story.

But while, compared to most films, the narrative of Spirited Away appears fragmented and confused, there is still a logic to it. Indeed, I would suggest it relies on several different types of logic. There are hints of a cultural logic in the film, a set of actions or events that make more sense in Japanese culture than in American culture. Obviously, nature spirits and bathhouse culture would fit into this category. More interestingly, I suspect that it is culturally meaningful that one of Chihiro’s most significant actions in the film is to apologize (and indeed, this is the act that takes up the penultimate 20 minutes of the film, where you would find the climax in a more traditional film). I’m not going to suggest that apology is a specifically Japanese value, but you certainly don’t see many American films—for children or for adults—that hinge on a good apology (Brave is a recent, and interesting, exception).

There is also a type of childish or children’s logic at work in the film. For example, when Haku attempts to sneak Chihiro into the bathhouse without detection, he explains that she will remain invisible to the spirits as long as she can cross the bridge without taking a breath. With this injunction, we find ourselves back in the realm of children’s superstition, where you have to hold your breath when passing a graveyard and where stepping on a crack can have dire consequences for your mother’s back.

Perhaps most importantly, Spirited Away relies on a type of dream logic, a chain of events and occurrences that are linked in ways that seem familiar from our own dreams. Chihiro’s legs stop working and become rooted to the ground. Characters look exactly like each other and even switch bodies. No Face tries to speak but cannot. Chihiro must carefully climb down a perilous flight of stairs and, later, scale a huge ladder. Sumptuous buffets of food appear from nowhere. Indeed, even just typing these examples, I feel anxiety as I recognize these moments from my own dreams. The narrative’s reliance on dream logic is made explicit with Chihiro’s attempt to explain to herself what is going on. As her parents transform into pigs and she finds herself trapped on the bathhouse island, she repeatedly insists “I’m dreaming! I’m dreaming!” But she’s not. Chihiro’s narrative (unlike those of Alice and Dorothy) is not a dream; it just acts like one.

This is where, I think, the problem of memory comes in. I suspect that it’s hard for me to remember the plot of Spirited Away for the same reason that it’s hard for me to remember my own dreams. And the problem here is the “why.” Often when I’m recounting my dreams to other people, I find myself saying things like “I don’t remember why, but you turned into a vampire” or “I don’t remember why, but we were at my elementary school.” But without the why, it’s hard for me to make sense of a dream—lacking sense, my memory of it devolves into a few arresting images. And indeed, there are plenty of missing “whys” in Spirited Away. Why is the enchanted bathhouse in the middle of an abandoned amusement park? Why do humans become trapped there at sundown? Why does Lin look like a human when none of the other spirits do? Why did Yubaba take an oath to hire anyone who asks for a job? Why does No Face go crazy and start eating everything? I could go on.

And yet, while there is something mildly anxiety-provoking for me about the dream logic in this movie, I wouldn’t describe Spirited Away as scary or suspenseful. Scares and suspense rely on an expectation of the bad thing that you know is going to happen, even if you don’t know quite when it’s going to happen. Spirited Away, in contrast, offers a narrative in which I literally have no idea what could happen next: it could be good, it could be bad, it could be weird, or it could be an apology. There is something uncomfortable about this state, of course, but it also replaces the dread of suspense with a simple curiosity about unpredictability.

Which is not to say that there aren’t unsettling and spooky moments in the film. Inside the bathhouse, there is an almost obsessive focus on bodies in their full and troubling fleshiness—including the obese turnip with nipples who follows Chihiro around. There are spectacles of appetites horribly out of control. There is the giant baby and the very real threat of his infantile desires (“Play with me or I’ll break your arm!”). There is the strange twinship of Yubaba and Zaniba—who, I began to suspect by the end of the film, may not actually be separate characters. And there is the inarticulate “uh, uh” sound produced by No Face, which caused my partner to murmur “creepy” on more than one occasion during our viewing. In other words, this is the realm of the uncanny and it’s odd territory for a film famously written for ten-year-old girls. After all, you don’t see many be-nippled tubers wandering around in the Olsen Twins oeuvre (Dave Coulier doesn’t count).

But just because Spirited Away isn’t a typical film for kids, that doesn’t mean it’s devoid of Important Lessons. If you were raised on American animation, however, the pedagogy in Spirited Away may slip past you—indeed, at no point does an animated character look out from the screen and say “Sharing is fun!” What makes Spirited Away refreshing is that it conveys its lessons gently, often in passing. And what does it teach us? Well, there’s respect for the environment (Haku is the lost spirit of the River Kohaku, which was filled in to build apartments). There’s the trouble with greed (No Face drives the bathhouse workers into a horrible frenzy by giving away gold). There’s a belief in the necessity of work (Chihiro must, like everyone else in the bathhouse, get a job in order to exist).

Probably the strongest lesson of the film is on the theme of self-reliance. Miyazaki clearly wants us to recognize that Chihiro’s adventure teaches her that she can take care of herself. And that lesson gives her the strength to face the coming adventures in her new town and at her new school. Indeed, her final words in the film are “I think I can handle it.” Yet, even this affirmation is curiously ambiguous. We could read it as meaning something like “I can do anything! Girl power!” (which is probably how the dialogue would read in an American film). But we could also read this line as meaning “I just had my parents turned into pigs and I was forced to bathe giant spirits. At least my new school won’t be as bad as that.” Chihiro’s final line hovers between confidence and resignation. And it is this uncertainty that ultimately makes Spirited Away smarter and more interesting than most animated films I’ve seen.

Spirited Away , or Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi (千と千尋の神隠し, “Sen and the spiriting away of Chihiro”) is an anime film, first released in Japan in 2001 , about a young girl who discovers a fantasy world where spirits live after her parents undergo a mysterious transformation.

I can’t find the movie on youtube